“You are what you eat…” Do you eat to live or live to eat? Much of our time in modern America is spent talking about what to eat, when to eat, where to eat. Worrying about what we are going to have for dinner.

And then there is all the conflicting nutritional information. Should you try the keto diet? The grapefruit diet? Apple cider vinegar? Eggs? Red wine? Coffee? This week we learned that tea may or may not be bad for you.

According to a 2017 study the most popular diets are the Atkins Diet, Zone Diet, Keto Diet, Vegetarian Diet, Vegan Diet, Weight Watchers, South Beach, Raw Food , and the Mediterranean diet. Which is right for you?

Judaism has much to say about food too. It elevates it. We celebrate with it. We turn food into symbols. Just think about the upcoming Passover. Bitter herbs, salt water, karpas, (parsley), charoset, all are symbols. Even the matzah itself. Especially the matzah itself.

Let all who are hungry come and eat…this is the bread of affliction, lechem oni, the poor bread.

This week in the parsha we learn more about keeping kosher. On the surface it would seem nonsensical. When I was in 7th grade Hebrew School, I learned that keeping kosher was an outmoded form of Judaism. Then we were taken to an antiquated deli and taught about blue soap and red soap. There must be someone who still kept kosher or there wouldn’t be red soap and blue. It wasn’t until college that I knew anyone who kept kosher.

One year when I was teaching 8th grade, I had a class that was really tough, as that age can be. They were not motivated at all to be there. Eventually we went to visit all of the professionals in the building asking them how they thought about their Judaism every day. I was surprised as we visited the secretary and janitor and the ed director and the cantor and the rabbi. No one thought about their Judaism. It just was. In desperation and exasperation, I said to the rabbi, “But you daven every day, must think about Judaism.” And he said, no. And then I asked about kashrut, that must make him think about Judaism every day. Now remember, this was the 90s. His answer, his wife took care of that.

Why these outdated laws about food? Why does it matter?

- Some argue that it is a commandment, so it is our obligation to just do it. There doesn’t have to be an underlying reason.

- Some argue that it was about food safety. If you don’t eat pork you can’t get trichinosis. Many are allergic to seafood. Creepy crawly things, well, just yuck.

There are a couple of other arguments. Because we’re Jews; we argue about everything:

- We are told that we as humans are sentient beings. We think. We feel. Keeping kosher is a way to be mindful. It provides a kavanah, an intentionality. It keeps us aware of our food. It reminds us that there is something higher out there. That we are dependent on others and G-d. It is a partnership.

- It turns meals into holy time. Time set apart. It slows us down. That’s why we say a blessing before we eat…and after.

- Keeping kosher, like mezuzah, Shabbat and circumcision, keeps us separate in another way as well—keeps us separate from others. It is harder to mingle with your non-Jewish neighbor if you are keeping kosher.

For me, it is about awareness. Mindfulness. And about welcoming anyone who may wish to eat in my home. And by extension, the synagogue. That was my initial reason for keeping kosher in college. So anyone could eat in my dorm room. And I still have those first plates, still with nail polish on the bottom marking the meat and dairy ones.

But that is not true for everyone. Kosher Nation, published in 2010 by Sue Fishkoff, we learn about the growing trend of keeping kosher. Here is the review:

“Kosher? That means the rabbi blessed it, right? Not exactly. In this captivating account of a Bible-based practice that has grown into a multibillions-dollar industry, journalist Sue Fishkoff travels throughout America and to Shanghai, China, to find out who eats kosher food, who produces it, who is responsible for its certification, and how this fascinating world continues to evolve. She explains why 86 percent of the 11.2 million Americans who regularly buy kosher food are not observant Jews—they are Muslims, Seventh-day Adventists, vegetarians, people with food allergies, and consumers who pay top dollar for food they believe “answers to a higher authority.””

So 86% of people buying kosher food aren’t observant Jews. What’s going on here? Muslims are looking to make sure there is no pork. So are the Seventh Day Adventists. Vegetarians are making sure there is no meat. When the doctors thought that maybe Sarah was lactose intolerant, we were told to purchase only parve food, food that would not include any dairy products and would be labeled as such. And then they added, “You already know about that.”

In this modern world, there are lots of reasons to focus on the spiritual aspects of food. Did you know that we are supposed to feed our animals first, before we sit down to eat? (Berachot 40a)

How many of you ate at least one meal in your car this week. I know I did. But Judaism tells us that we should not eat while we are standing. There are many explanations of this, https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/15580/forbidden-to-eat-while-standing-up

These days, there is much we can focus on about spirituality and eating. There is a whole movement toward ethical kashrut—across all the spectrum of Jewish religious observance. That modern day kashrut that may include considerations of

- The ethical treatment of both farm workers and animals

- Using fair trade when appropriate. That’s why I really only drink fair trade, kosher coffee and try to require it here in our kosher kitchen.

- Hosting a zero waste Passover

- What about the packaging we use? Or the dishes and the table clothes? What do we do with compostable waste?

- Making sure we really “let all who are hungry come and eat” be that our work with the Elgin Cooperative Ministries and the upcoming Soup Kettles, the Community Garden where we literally leave the corners of our field

- Exploring vegetarian and vegan options

- Recognizing the changing nature of wheat and providing gluten free options

What I have prepared for you to study are five different rabbis’ opinions about kashrut and why they are important to him (or her!). Divide yourselves into two groups and see what resonates. (The Source material follows)

Things we learned:

Rabbi Richard Israel: Kashrut makes me confront important questions about the ethical issues around food. That turns eating into a holy experience. That makes me holy, each of us holy.

Rabbi Harold Kushner: G-d cares about me, and the choices I make. Choosing to keep kosher makes me a little less than divine. Choosing to eat kosher makes us holy.

Rabbi Donin: It gives us a little bit of control. A little bit of balance and a way to begin to understand the divine mind. That makes us holy.

Rabbi Yankovitz: We have an obligation to treat animals and workers ethically. We have a unique responsibility here. Kashrut helps us understand the spiritual potential that food has. The kosher laws have a unique charge to holiness.

Rabbi Ruth Sohn: Kashrut is a spiritual discipline that connects us to G-d and to our past, to our tradition. Kashrut is our unique path to holiness: “for you are a people consecrated to your God.

One last reason…it enables us to be grateful. For the soil. For the seeds. For the sun and rain. For the very food that nourishes and sustains us. And for G-d and our relationship with the divine. For this we give blessings.

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha’olam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz. Blessed are You, Lord, our G-d, Ruler of the Universe who brings forth bread from the earth.

Let all who are hungry come and eat, as we continue to prepare for Passover.

My Jewish Learning:

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/keeping-kosher-contemporary-views/

Rabbi Richard Israel:

I find that whether I like it or not, kashrut brings me into contact with a series of rather important questions: What is my responsibility to the calf that I eat, or to the potato? Is the earth and the fullness thereof mine to do with as I will? What does it mean that a table should be an altar? Is eating, indeed, a devotional act? Does God really care whether I wait two or six hours before drinking milk after a meat meal? If kashrut makes me ask enough questions, often enough, I discover that its very provocative quality is one of its chief virtues for my religious life.

Rabbi Harold Kushner

Let’s go back to my hypothetical lunch with a friend. Watching me scan the menu, he may suspect me of thinking, “Oh, would I love to order the ham, but that mean old God won’t let me.” But in fact, what is probably going through my mind at the moment is “Isn’t it incredible! Nearly five billion people on this planet, and God cares what I have for lunch!” And God cares how I earn and spend my money, and whom I sleep with, and what sort of language I use. (These are not descriptions of God’s emotional state, about which we can have no information, but a way of conveying the critical ethical significance of the choices I make.) What better way is there to invest every one of my daily choices with divine significance? There is nothing intrinsically wicked about eating pork or lobster, and there is nothing intrinsically moral about eating cheese or chicken instead. But what the Jewish way of life does by imposing rules on our eating, sleeping, and working habits is to take the most common and mundane activities and invest them with deeper meaning, turning every one of them into an occasion for obeying (or disobeying) God. If a gentile walks into a fast-food establishment and orders a cheeseburger, he is just having lunch. But if a Jew does the same thing, he is making a theological statement. He is declaring that he does not accept the rules of the Jewish dietary system as binding upon him. But heeded or violated, the rules lift the act of having lunch out of the ordinary and make it a religious matter. If you can do that to the process of eating, you have done something important.

Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin

The faithful Jew observes the laws of kashrut not because he has become endeared of its specific details nor because it provides him with pleasure nor because he considers them good for his health nor because the Bible offers him clear-cut reasons, but because be regards them as Divine commandments and yields his will before the will of the Divine and to the disciplines imposed by his faith. In the words of our Sages, “A man ought not to say ‘I do not wish to eat of the flesh of the pig’ (i.e., because I don’t like it). Rather he should say, ‘I do wish to do these things, but my Father in Heaven has decreed otherwise.’”

Although “the benefit arising from the many inexplicable laws of God is in their practice, and not in the understanding of the motives” (Moses Mendelssohn), nevertheless the Jew never tires of pursuing his quest to fathom the Divine Mind and to ascertain the reasons that prompted the promulgation of God’s laws. For the man of faith is sure that reasons do exist for the Divine decrees even if they are concealed from him.

Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/ethical-kashrut/

The first act of food consumption in the Bible is also the Torah ’s first foray into ethics. God instructed Adam and Eve to eat from any tree but the Tree of Knowledge. The human inability to restrain desire led to the possibility of sin. The first human beings ate the forbidden fruit, and the need for ethical standards was born.

Since then, halacha (Jewish law) has functioned to make its adherents understand the spiritual potential that food can have in one’s life. By legislating various practices such as making berakhot (blessings) before and after eating food, distinguishing between dairy and meat meals, separating dishes, and drinking wine and eating bread on holidays, Jewish law highlights the significance of food in life.

In the first decade of the 21st century, a growing movement emerged focusing not only on ritual, but also on ethical kashrut . This movement emphasizes not only the traditional rules, but also takes into account issues such as animal treatment, workers conditions, and environmental impact, taking its cue from a number of supporting biblical sources:

How do these new “rules” of ethical kashrut relate to the traditional rituals, blessings, and separation of dishes? Many of those who observe kashrut believe that the values of ethical kashrut may have been the original intention for how religious food consumption was prescribed in the Torah. For others, these values are a positive expansion or evolution from the traditional rules. For still others, the contemporary values of ethical kashrut can replace the old, harder-to-understand rituals.

The Torah and other Jewish literature lend support for ethical kashrut initiatives. Nahmanides, a 13th century Spanish rabbi, argued (Leviticus 19:1) that if people consume food that is technically kosher from a ritual perspective but do not embrace the ethics that come along with consumption then they are naval birshut haTorah(despicable with the permission of the Torah). They have broken no formal kashrut prohibitions but their act is shameful, and they have not lived by the moral and ethical intentions of the Torah. Nahmanides is referring to eating in moderation but his value certainly lends to broad extension. Simply put: permissible consumption does not necessarily mean good consumption.

1.The Jewish community has already demonstrated immense success using money and power to build the kosher certification system. This infrastructure and model can just as easily be used for ethical certification and awareness.

2. As Jews, we have ownership and responsibility over the kashrut industry.

3. The laws of kashrut have a unique charge to pursue holiness.

Rabbi Ruth Sohn https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-purpose-of-kashrut/

“You are what you eat’ the common expression goes. I sometimes think of this saying in relation to kashrut (that is, keeping kosher). What do the choices that we make about what we eat reveal about who we really are? Many Jews today view kashrut as an outdated vestige of ancient Israelite practice, expanded upon by rabbinic Judaism, bur no longer relevant to modern day life. ..However, the presentation of the prohibitions associated with kashrut in Parashat Re’eh challenges us to consider anew the purposes of kashrut. Deuteronomy 14 tells us what animals, fish, and birds we can and cannot eat. It instructs us not to boil a kid (a young goat) in its mother’s milk, an injunction that became the basis for the rabbinic separation between milk and meat (Deuteronomy 14:21; see also Exodus 23:19 and Exodus 34:26). While many Jews today believe the biblical prohibitions against certain meat and fish to be for health reasons, Parshat Re’eh makes no such claim. In fact, if this were the case, the explicit permission to give the stranger and the foreigner the foods we are forbidden to eat (Deuteronomy 14:21) would be frankly immoral. Rather, Parshat Re’eh, as the Torah does elsewhere, identifies the articulation of eating prohibitions strictly as part of the Israelites’ particular path to holiness: “for you are a people consecrated to your God Adonai” Deuteronomy 14:21). What is it about these prohibitions that can make us holy? Interestingly, the prohibited foods are identified as tamei … lachem–ritually impure “for you” (Deuteronomy 14:7, 8, 10). For this reason, it is perfectly acceptable for other people to eat them, just not for the people Israel.

A Spiritual Discipline

Traditional and modern commentators have offered various explanations as to why particular fish, poultry, and animals are considered tahor (“ritually pure”) and therefore acceptable to eat. But perhaps more important than the meaning of each of the details of the prohibitions is the simple fact that we are given a list of dos and don’ts that govern what we are to consume daily. According to the Torah, God asks that we abstain from eating certain foods, not because they are unhealthy or intrinsically problematic, but simply as an expression of our devotion. As with other chukim (laws that the rabbinic sages define as being without rational explanation), these prohibitions are like the requests of a beloved: we may not understand them, but we are, in essence, asked to follow them purely as an expression of our love. Daily, the observance of kashrut calls us back to a personal relationship with God. The laws of kashrut offer a Jewish spiritual discipline that is rooted in the concrete choices and details of daily life — to be practiced in an area that seems most “mundane.” In fact, part of the beauty of kashrut is that regardless of our age, personal interests, or geographic location, we all eat, and most of us do so several times a day. While we may sometimes choose to dine alone, eating is almost universally enjoyed as a social activity. A spiritual discipline around eating is one that carries the clear message that spirituality is about far more than what we do in synagogue and on holidays; it extends into every area of our lives, every single day.

Kashrut reminds us again and again that Jewish spirituality is inseparable from what one might term “physical.” It teaches us that Jewish spiritual practice is about taking the most ordinary of experiences — in all aspects of our lives — and transforming them into moments of meaning, moments of connection. Kashrut provides a model for doing just that, around issues of food preparation and eating. It’s time to cook dinner: What will we make, and how will we prepare it? Will we be driven by an empty stomach or considerations that extend beyond it as well? In these moments, kashrut can connect us to Jewish tradition, to other Jews, and to God. We are hungry and sit down for a meal, but before digging in, we recall that Jewish tradition offers us the practice of pausing for a blessing and a moment of gratitude. We may take this a step further and decide to put aside tzedakah regularly at dinnertime, as some of us try to do. This can be seen as a practice similar to the tithing performed in ancient times, as outlined in the verses immediately following the rules of kashrut in our Torah portion (Deuteronomy 14:22-29). Instead of just wolfing down our food and moving on to the next activity, we can learn from Jewish rituals to pause and turn the act of eating into a moment of heightened spiritual awareness.

Bringing Contemporary Concerns to Kashrut

Increasing numbers of Jews today are expanding their kashrut practice to incorporate additional ethical and environmental considerations. Was the food produced under conditions that respect persons and the environment? Were the workers who picked or prepared the food paid a living wage? Did the processes of production treat animals humanely? In addition to allowing these questions to influence our choices about what to eat, we can direct our tzedakah money to organizations that address these issues, like environmental and farmworker advocacy groups.

From the time of the Torah onward, Jewish tradition teaches us that the spiritual realm encompasses all of life. Kashrut and the other Jewish practices related to eating exemplify this teaching and extend beyond themselves: they stand as daily reminders to look for additional ways to turn the ordinary into moments of deeper connection and intentionality. Every moment has the potential to be one of connection. Through other mitzvot, such as the laws governing proper speech and interpersonal ethics, as well as through the less well-known but rich Jewish tradition of cultivating middot (personal qualities such as patience and generosity in judgment), we can seek to deepen our connections with each other and with God. A Jewish spiritual discipline around eating, practiced with intention, can set us on this course every day. “You are what you eat.” That is, what you choose to eat and how you choose to eat it says a lot about who you are and what kind of a life you are striving to achieve.

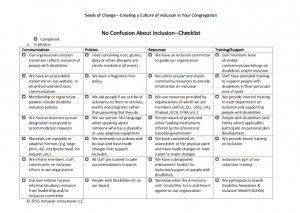

She asked what does inclusion mean to you. For me it is about living out our vision statement that includes “Embracing Diversity.” All are welcome here. With all our varying abilities and disabilities.

She asked what does inclusion mean to you. For me it is about living out our vision statement that includes “Embracing Diversity.” All are welcome here. With all our varying abilities and disabilities.